Stress-induced protein disaggregation in the endoplasmic reticulum catalysed by BiP

By Eduardo Pinho Melo, Tasuku Konno, Ilaria Farace, Mosab Ali Awadelkareem, Lise R. Skov, Fernando Teodoro, Teresa P. Sancho, Adrienne W. Paton, James C. Paton, Matthew Fares, Pedro M. R. Paulo, Xin Zhang & Edward Avezov

Excerpt from the article published in Nature Communications 13, 2501 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30238-2

Editor’s Highlights

- The biosynthetic organelles evolved a multi-layer proteostasis network (PN) that chaperones nascent proteins and rescues or recycles misfolded intermediates.

- Shortfalls of the PN machinery may lead to pathology: protein aggregation accompanies neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia.

- In the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) where ~30% of the proteome is synthesized, the branch of the PN, the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR), alleviates un/misfolded protein load during stress by transient attenuation of protein synthesis and posttranslational chaperone activation, followed by transcriptional upregulation of protein maturation and quality control factors.

- The three-layered PN response explains the ER’s ability to maintain high fidelity protein manufacturing inducing disaggregation in a space crowded with nascent/folding species.

- The BiP system appears the only ER-resident molecular machine with such a potential.

- Mechanisms of BiP repurposing from a holdase/foldase-like chaperone to a disaggrease may hold clues to identifying strategies for antagonizing toxic aggregates/seeds that evade the unstressed system (e.g. A-beta oligomers).

Abstract

Protein synthesis is supported by cellular machineries that ensure polypeptides fold to their native conformation, whilst eliminating misfolded, aggregation prone species. Protein aggregation underlies pathologies including neurodegeneration. Aggregates’ formation is antagonised by molecular chaperones, with cytoplasmic machinery resolving insoluble protein aggregates. However, it is unknown whether an analogous disaggregation system exists in the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) where ~30% of the proteome is synthesised. Here we show that the ER of a variety of mammalian cell types, including neurons, is endowed with the capability to resolve protein aggregates under stress. Utilising a purpose-developed protein aggregation probing system with a sub-organellar resolution, we observe steady-state aggregate accumulation in the ER. Pharmacological induction of ER stress does not augment aggregates, but rather stimulate their clearance within hours. We show that this dissagregation activity is catalysed by the stress-responsive ER molecular chaperone – BiP. This work reveals a hitherto unknow, non-redundant strand of the proteostasis-restorative ER stress response.

Introduction

Newly synthesised polypeptides must attain the functional three-dimensional conformation, thermodynamically encoded by the amino acid sequence1. Protein folding describes the process where polypeptides seek the minimum point in energy-funnel but can be trapped in local minima separated by low barriers (misfolding traps2). Furtherer, the chemical diversity and crowdedness of cellular compartments create conditions for reactions competing with native folding, inducing local unfolding and stabilising non-functional, misfolding-trapped conformations. Unfolded and misfolded protein species tend to form insoluble aggregates3. To avoid the accumulation of cytotoxic aggregates, the biosynthetic organelles (i.e. cytoplasm, the Endoplasmic Reticulum, ER, and mitochondria) evolved a multi-layer proteostasis network (PN) that chaperones nascent proteins and rescues or recycles misfolded intermediates4. The PN is endowed with a capability to feedback to the gene-transcription and translation systems to interactively adjust the protein production rate to its folding-assistance and quality control capability. The ER branch of the PN, the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR), alleviates un/misfolded protein load during stress by transient attenuation of protein synthesis and posttranslational chaperone activation, followed by transcriptional upregulation of protein maturation and quality control factors5,6.

Shortfalls of the PN machinery may lead to pathology: protein aggregation accompanies neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia7. Neuronally expressed metastable proteins (e.g. Aβ, Tau, or α-synuclein)—with a tendency to oligomerise and consequently aggregate—underlie these conditions. The late onset of the aggregation-related sub-populational neurodegeneration is consistent with age- and environmental factor-dependent decline in the efficiency of the PN machinery. Understanding how the cell handles aggregation-prone proteins on an organellar level is crucial to rationalising the disease-related proteostasis impairment.

The recent discovery of the cytosolic Hsp70 chaperone and its assisting system’s capacity to resolve cytoplasmic aggregates8 (including amyloids9,10) adds another functional layer to the PN for rectifying imperfections of the quality control system or prion-like transition from native folding to aggregation. However, it is unknown whether such a capability exists in the ER—a site responsible for the manufacturing of about one-third of the cell’s protein repertoire (including disease determinants, e.g. amyloid precursor protein, APP). Observations suggest that the chaperone-rich environment of the ER is more immune to protein aggregation than the cytoplasm11. How the organelle maintains high fidelity protein folding, avoiding aggregation throughout the lifetime of the cell, particularly the non-dividing neurons, remains an open question. Explaining this in terms of protein folding quality control alone would rest on the assumption that the system can achieve zero aggregation and absolute quality control through astronomically large numbers of protein folding cycles.

In this work, we use a purpose-developed protein aggregation probing system with sub-organellar resolution to show accumulation of protein aggregates in the ER. Strikingly, ER stress, induced by N-glycosilation or Ca2+ pump inhibitors, triggers an aggregates’ clearance activity. We find that protein dissagregation is catalysed by the stress-responsive ER molecular chaperone—BiP. Modulating its amount in the ER reveal an inverse correlation between BiP’s presence and the aggregation load. Further, we reconstruct the disaggregation reaction in vitro by a minimal system of ATP-fuelled BiP with a J-domain cofactor.

Results and discussion

Monitoring ER protein aggregation in live cells

We sought an optical single-cell protein aggregate probing approach with subcellular space resolution to surmount limitations associated with biochemical, post-lysis cell population extracts. The lysate-probing techniques can detect aggregation events in a population involving drastic changes in a high proportion of an aggregating protein. However, the heterogenous population averaging effect in ensemble analyses, combined with the lack of information on the probe’s distribution in space and the reliance on protein status preservation in lysis limit the ability to resolve folded/misfolded/aggregated species of metastable substrate. The folding status of metastable reporter-protein, which can assume either state, can reflect the activity of the cellular protein folding handling machinery. Thus, to address how the ER handles protein folding/aggregation, we established an optical approach to monitoring this process in live cells based on a cell-inert metastable surrogate protein. The protein core of the probe is an E. coli haloalkane dehydrogenase variant destabilised by mutagenesis and covalently modifiable by a solvatochromic fluorescent moiety (Fig. 1a)12 HT-aggr herein. As HT-aggr has no natural function and interactors in the ER, its fate (in terms of folding, aggregation, and degradation) is exclusively reflective of the protein-handling activity in the host organelle.

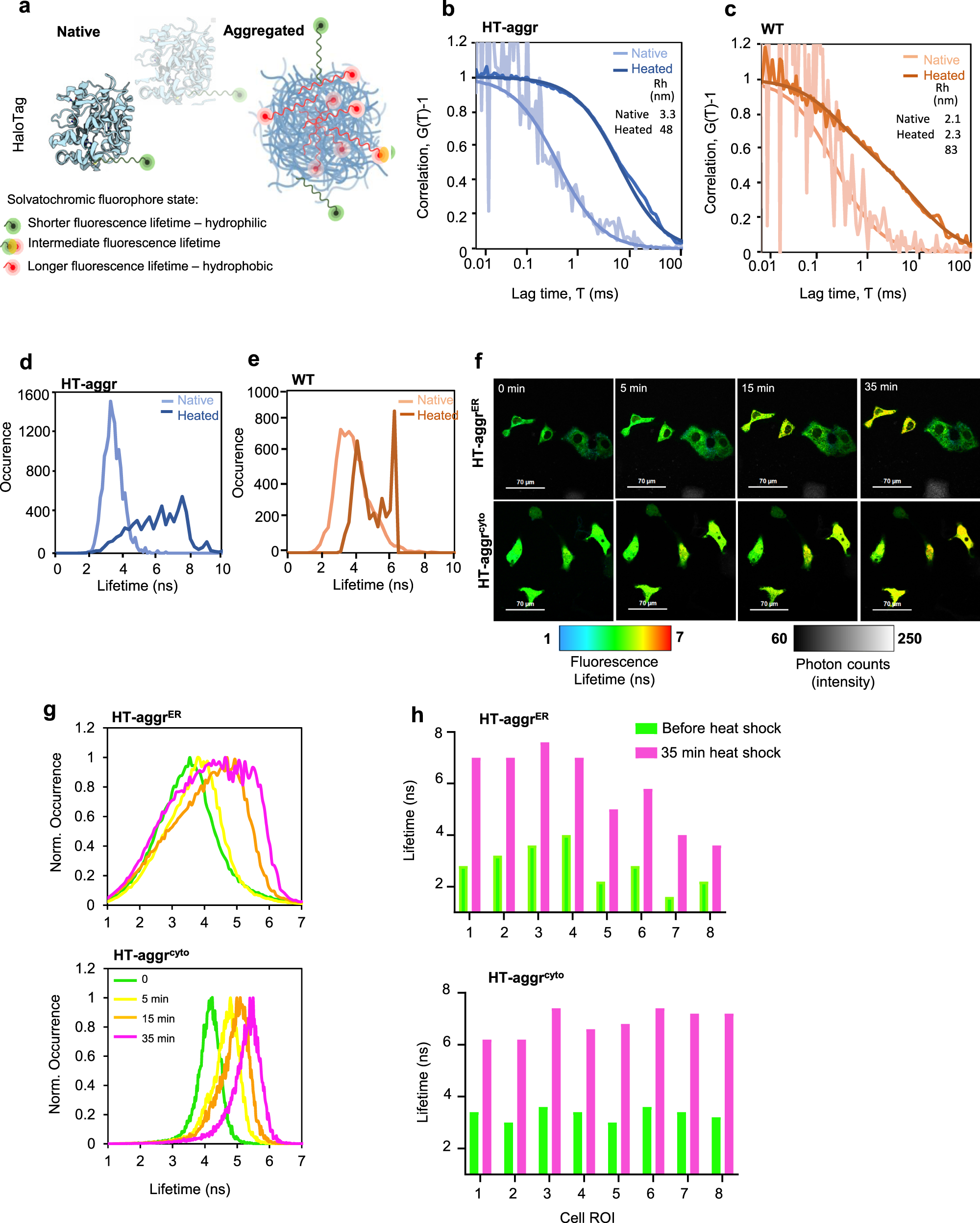

Fluorescence lifetime-based probing system for real-time monitoring of protein aggregation.

a Schematic representation of the HT-aggr probing system. b Normalised autocorrelation function (G(τ) − 1) from fluorescence correlation spectroscopy measurements of purified, native or heat-aggregated HT-aggr (K73T) probe or (c) HaloTag wild type (HT-WT), labelled with the solvatochromic fluorophore P114. Solid lines represent best fits of the autocorrelation function considering a single species for HT-aggr and HT-WT, and two species for heat-aggregated HT-WT, as shown by the hydrodynamic radius values in the inset. d, e Fluorescence lifetime histograms of samples in (b, c), respectively. f A time series of live-cell fluorescence lifetime micrographs (FLIM) of HT-aggr (K73T) transiently expressed in the ER or cytoplasm of COS7 cells, before and after exposure to a heat-shock treatment (43 °C), representative images from three independent experiments. g Fluorescence lifetime histograms from image-series shown in f, (green, yellow, orange and pink traces represent the time points before, 5-, 15- and 35-min heat shock, respectively). h fluorescence lifetime values of individual cells as in (f).

The aggregation propensity of the HT-aggr probe is predicted by a relatively low unfolding free energy value (ΔG0unf decreased from 5.6 kcal/mol in HT-WT to 2.0 kcal/mol in HT-aggr K73T, Supplementary Fig. 1). This metastability—propensity to aggregate, was reflected in fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) measurements: upon heating in vitro, HT-aggr formed particles with a hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of 48 nm, while HT-WT only partially aggregated under the same conditions displaying a biphasic FCS trace, which represents putative monomers and larger aggregates (the predicted Rh of a globular 26-kDa HT of 2.9 nm agrees with the FCS-measured monomer size of 2–3 nm, Fig. 1b, c, consistent with13). Further, we observed an increase in the solvatochromic fluorophore’s fluorescence lifetime attached to aggregating probe species (Fig. 1d, e). The native HT-aggr and HT-WT showed a unimodal distribution of lifetimes peaking at ~3.3 ns that broadened and shifted upon heating to longer lifetime values with a jagged plateau between 4.9 and 7.6 ns for HT-aggr (Fig. 1d) and two distinct peaks for HT-WT (Fig. 1e) corresponding to monomers and large aggregates, apparent in the FCS traces (Fig. 1c). This equivalence between the probe’s fluorescence lifetime and aggregation state (Fig. 1a) provides means for monitoring the state of the aggregation probe in live cells by Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM). This methodology offers an accurate and absolute measure of the probe’s state, free from the confounding effects of intensity calibrations and photo-bleaching14,15,16, thus removing the limits associated with the intensity-based readouts. Based on the probe’s in vitro performance, we sought to establish FLIM-based measurements of its folding/aggregation status in live cells. Consistent with the in vitro measurements, heat-stress triggered aggregation of HT-aggr, transiently expressed in the cytoplasm or ER, as registered by an increase in probes’ fluorescence lifetime (Fig. 1f, g). This behaviour was not observed for HT-WTER (Supplementary Fig. 2). In line with previous observations11,17, the ER appeared more resilient than the cytoplasm in maintaining HT-aggr soluble in heat-shocked cells, as reflected by an attenuated shift towards longer fluorescence lifetime in the ER, compared to cytoplasm-resident probe. Notably, the increase in fluorescence lifetime of the ER-targeted probe upon heat shock is considerably more heterogeneous in magnitude across the cell population than that of the cytoplasmic probe (Fig. 1h). This points to greater resilience of the ER to protein aggregation in some cells (compare HT-aggrER to HT-aggrcyto in Fig. 1h, note the presence of more/less heat-sensitive HT-aggrER cells reflected in their yellow/green FLIM-appearance, respectively). As ER-localised proteins undergo N-glycosylation if their sequence contains an exposed Asp-X(except Pro)-Ser/Thr tripeptide, a modification that could alter HT-aggr properties, we confirmed that HT sequence is devoid of this signal.

To assess the long-term kinetics of the HT-aggrER aggregation, we delivered its encoding vector in a retroviral vehicle driving genomic integration and thus stable expression. Tracking the aggregation status post-infection, we observed that prolonged expression of the probe in the ER led to spontaneous HT-aggr aggregation with an accumulation of large aggregate particles (apparent as red puncta—lifetime >5 ns, similar to the aggregates’ values in vitro, Fig. 2a). Notably, the population of pixels with regular (non-punctate) ER-pattern also showed a longer lifetime (pixels in the yellow spectrum), presumably reflecting smaller sub-diffraction limit aggregation intermediates/oligomers mixed with native probe (mixture of green and red, Fig. 2a, b). The fraction of cells with FLIM-detectable aggregates (red puncta) increased with time up to 9 days (Fig. 2c). From that point on, the size distribution of the aggregates drifted with time towards larger particles (Fig. 2d), indicating a further accumulation of aggregated material.

Intra-ER accumulation of non-toxic aggregates of the metastable HT-aggr.

a Time series of FLIM micrographs of CHO-K1 cells post stable retroviral infection with ER-targeted HT-aggr probe (K73T), labelled with P1 fluorophore. ER-targeting of HT as in ref. 36. b Plot of mean fluorescence lifetime values of HT-aggrER/P1 for the time points in (a). c Plot of the percentage of cells with FLIM-detectable aggregates (lifetime > 5 ns, apparent as red puncta, the threshold set to visualise aggregates in nearly monochromatic) from image-series as in (a). d Frequency distribution of aggregates’ sizes extracted from FLIM time-series as in (a) using the Aggregates Detector, Icy algorithm. (shown in (b, c) are values of mean ± SEM, n = 7 independent fields of view with at least 20 cells each). e High-resolution fast 3D FLIM image projections of CHO-K1 cells with HT-aggrER/P1. f FLIM images of live CHO-K1 cells stably expressing HT-WTER or HT-aggrER variants with various degrees of metastability, as indicated by Gibbs free energy values of unfolding (ΔG0Unf), (h) inset. g Plot of relative cell area occupied by FLIM-detected aggregates (lifetime > 5 ns, red puncta) quantified for the HT-aggr variants from images as in (f). (mean ± SEM, n = 3 independent fields of view, 60, 42, 55 and 45 cells analysed for WT, K73T, L172Q and M21K F86L variants, respectively). h Plot of relative cell area with aggregates (a measure of aggregation from (g) for each variant) as a function of its metastability, represented by the equilibrium constant of unfolding, expressed as KUnf = exp(−ΔG0Unf/RT)21, where ΔG0Unf is the free energy of unfolding (inset). i Growth curves for CHO-K1 cells expressing the HT-aggrER variants (WT, cyan; K73T, yellow; L172Q, orange; M21KF86L, red) along with parental cells (magenta). Solid lines are the fits for the exponential growth according to the equation % conft = % conft0 2 (t/td), where td is the doubling time. Individual values and standard deviations of td calculated from triplicates are shown in the inset. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, unpaired T test (two-tailed).

To establish whether the aggregated species accumulate in the ER lumen or post-retro-translocated into the cytoplasm, we implemented the Lightening super-resolution approach coupled to 3D FLIM enabled through a considerable improvement in the speed of the time-correlated single-photon counting of this modality18. Both the large, puncta-like aggregates (lifetime range in red) and the intermediates (lifetime range in yellow) showed a complete intra-ER localisation in the high-resolution fast 3D FLIM (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Movie 1). Consistently, inhibition of retro-translocation19 did not abolish the aggregates’ formation (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Further, co-localisation analyses of the aggregates’ signal with an ER marker in untreated cells and upon inhibition of retro-translocation showed a similar ER population in both conditions (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). A high degree of co-localisation between an ER marker and the whole HT-aggrER population was also measurable in normal conditions and upon retro-translocation inhibition (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Thus, HT-aggrERdoes not accumulate in the cytoplasm post-retro-translocation (unsurprisingly, as for most ER proteins, degradation is coupled to retro-translocation of ER-associated degradation, ERAD20).

Further, the extent of intracellular aggregation of the HT-aggrER variants (cell area fraction occupied by aggregates) correlated linearly with their unfolding equilibrium constant, a measure of their unfolding fraction21 (Fig. 2f–h). The differences in thermodynamic stability of HT-aggr variants explain the degree of aggregation-propensity of the HT-aggr variants Fig. 2h, inset). The properties of HT-aggr K73T suggest it as a useful variant for monitoring the capacity of the cellular protein folding quality control: This milder aggregation-prone probe showed expression levels at a steady-state similar to HT-WT (Supplementary Movie 2 for HT-aggr K73T and Supplementary Movie 3 for HT-WT), and a relatively low, but detectable ER aggregates’ load. Thus, FLIM of HT-aggr provides a space/time-resolved measure of aggregation in live cells, revealing that the chaperone-rich ER is not immune to protein aggregation—unfolded/misfolded intermediates of a metastable substrate may evade the folding quality control system accumulating over time in sizeable intra-ER aggregate particles.

The unfolded/misfolded intermediates of the probes and the aggregates that they give rise to were well tolerated with no cost to cell proliferation rates (Fig. 2i) and did not trigger a measurable increase in UPR activity at any point of the aggregate accumulation period (Supplementary Fig. 4).

ER stress-induced aggregates’ clearance

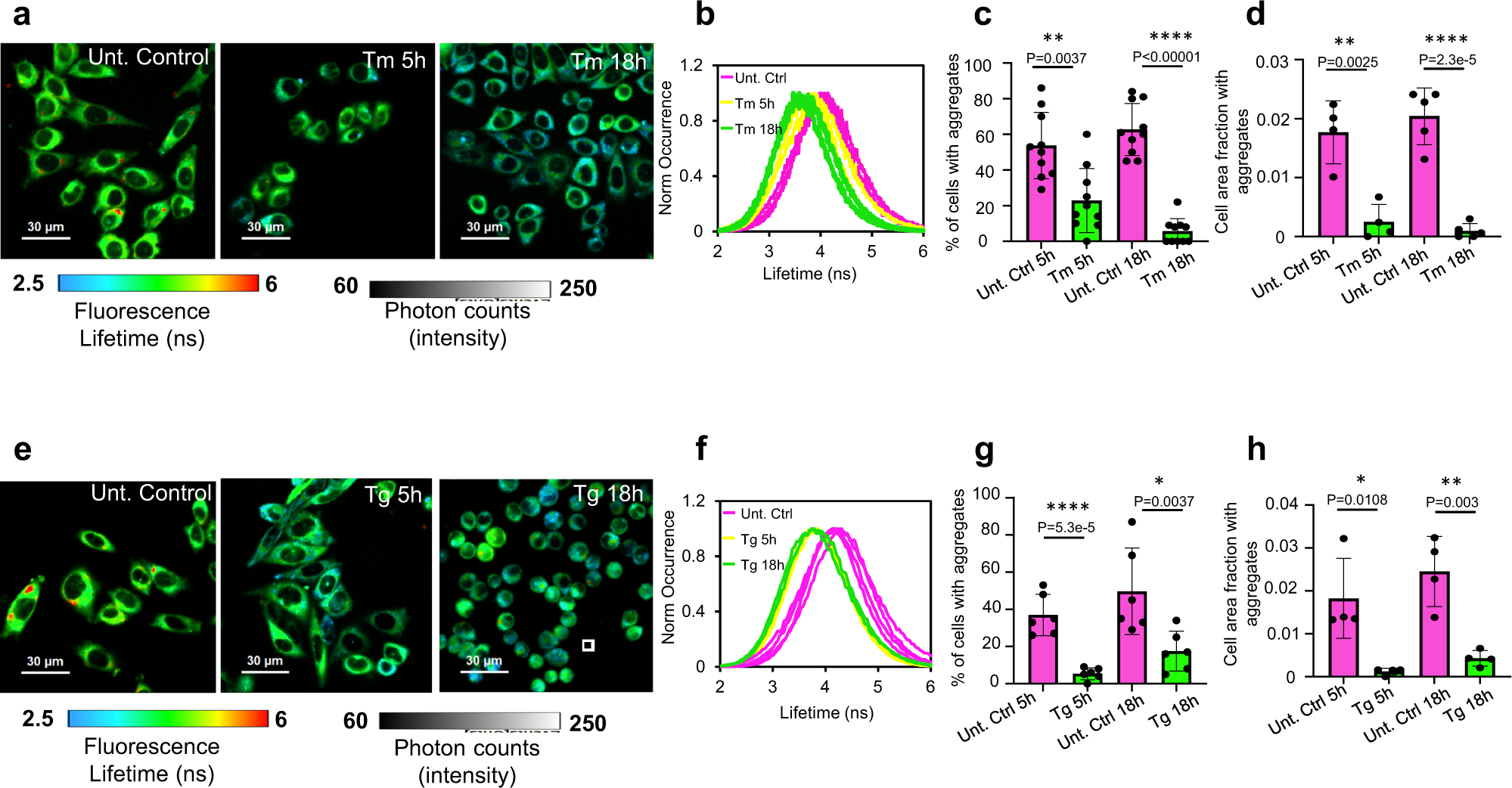

Surprisingly, imposing ER stress pharmacologically did not increase the aggregated fraction of the probe (Fig. 3). In these experiments, we pulse-labelled the probe with its fluorescent reporter-ligand and chased the fate of its labelled sub-population over time in the presence or absence of various treatments (i.e. stress inducers, degradation blockers). This mode allows dissecting the aggregation, disaggregation and degradation events which the model protein is undergoing. Namely, short exposure to the fluorescent HT-ligand labels a sub-population of pre-existing probe species, the fate of which is then traced, unmixed from the total population that includes species produced during the chase period (the dark probe). Strikingly, ER stress induction decreased the intra-ER aggregation: a pulse-labelled population of HT-aggrER showed a substantial shortening of fluorescence lifetime (Fig. 3a, b). The aggregated fraction substantially reduced in a time-dependent manner following the induction of unfolded protein stress, through the inhibition of nascent proteins’ N-glycosylation by tunicamycin (Tm, Fig. 3c, d, see ER stress markers’ induction and dose/time tests in Supplementary Fig. 5a, b, respectively). The diminished aggregation load manifested in a lower percentage of cells that show large puncta-like aggregate particles (lifetime > 5 ns, stand out as red colour coded pixels, Fig. 3a, c), and shrinking of the area occupied by these large aggregates (Fig. 3d). Moreover, in the FLIM images of tunicamycin treated cells, the entire distribution of pixels’ fluorescence lifetime gradually shifted towards lower values in nearly all the cells (Fig. 3b). This indicates that the longer lifetime oligomeric intermediates of the probe (too small to be detected as puncta) are also cleared. A similar effect was observed for the most aggregation-prone HT-aggrER variant M21K-F86L (Supplementary Fig. 6). Further, the probe faced a similar fate in human cortical neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC): in these cells, too, HT-aggrER formed puncta-like aggregates with a longer lifetime, whilst ER stress induction by tunicamycin lowered the aggregation load (Supplementary Fig. 7). Next, we examined the same aggregation parameters in cells prior and after induction of ER stress by other means—depleting ER calcium through its SERCA-ATP-ase pumps inhibition by thapsigargin. The aggregates clearance in these ER stress conditions was also evident through a shift of probe’s fluorescence lifetime pixel distributions towards shorter values, decreased fractions of cells with aggregates and a contraction of the cell area occupied by aggregates (Fig. 3e–h).

Pharmacological ER stress induction activates protein disaggregation machinery.

a, e FLIM images of live CHO-K1 cells stably expressing HT-aggrER, untreated or treated with tunicamycin (Tm at 0.5 µg/mL) or thapsigargin (Tg at 0.5 µM) for a time period post-pulse-labelling with the P1 fluorochrome as indicated. b, f Histograms representing frequency distribution of pixel fluorescence lifetime from image-series as in (a, e), note the shift towards shorter lifetime values post-treatment (traces represent individual cells, untreated control, pink; 5 h treatment, yellow; 18 h treatment, green). c, g Quantitation of the relative number of cells with FLIM-detected aggregates in images as in (a, e). d, hPlots of relative cell area occupied by FLIM-detected aggregates (lifetime > 5 ns, red puncta) in images as in (a, e). Mean ± SEM, n = 10, 5, 6, 4 independent fields of view containing at least 12 cells each (c, d, g, h), respectively. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, unpaired T test (two-tailed).

As the pulse-chase mode of imaging excludes the contribution of changes in aggregates formation from newly synthesised species, the surprising effect of imposed ER stress on the abundance of the probe’s aggregated fraction is explainable by the activation of mechanisms that enhanced protein degradation by autophagosomal/lysosomal machinery or by a disaggregation activity in the ER (hitherto unknown). Presumably, proteasome-mediated elimination of the ER-aggregated probe should also require its disaggregation prior to retro-translocation to the cytoplasm, where proteasomes reside. To distinguish between the two scenarios, we first investigated the turnover of HT-aggrER under non-stress and stress conditions. The ER quality control machinery attends to the misfolding-prone substrates—it lowers the variants’ expression by increasing their turnover (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 8, Supplementary Movie 2 and Supplementary Movie 3). However, the induction of ER stress slowed down the degradation rates of the WT-HT and HT-aggrER probes’ variants (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 8, Supplementary Movie 4 and Supplementary Movie 5). Besides, aggregate clearance evolved on a faster time scale than the probes’ degradation in stress (Fig. 3, Table 1). Furthermore, the aggregate reduction effect of the ER stress was insensitive to autophagosomal/lysosomal blockers (Supplementary Fig. 9). Therefore, the protein aggregation-antagonising effect of ER stress cannot be explained by enhanced autophagosomal/proteasomal degradation but consistent with the organelle’s active disaggregation activity.

Table 1 Turnover of HTER variants, labelled with tetramethyl-rhodamine Halotag ligand (TMR, 250 nM, 6 h), following the label removal, the samples were chase-imaged in the absence or presence of an ER stressor, tunicamycin (Tm, 0.5 µg/mL).

| HTER variant | Untreated t1/2 (hours) | t1/2 in Tm-induced stress (hours) |

|---|---|---|

| WT | 41 ± 9 | 174 ± 21 |

| K73T | 32 ± 3 | 58 ± 7 |

| L172Q | 7 ± 2 | 27 ± 5 |

| M21KF86L | 28 ± 11 | 15 ± 3 |

mpact of modulating BiP levels on the aggregation load in the ER

To this point, monitoring the fate of the HT-aggrER reveals an inducible capability of the ER to resolve protein-aggregates formed from a fraction that eluded the organelle’s quality control. This raises the question as to the identity of the ER disaggregation catalyst(s). In the cytoplasm, the chaperone network of Hsp10022 (absent in metazoans) and Hsp70, fuelled by ATP, can catalyse the solubilisation of protein aggregates8,9,10. The notions that the latter is the only currently known mammalian machinery with evidence of disaggregation activity through a plausible energetics/mechanics8,9,10, and that parallel functioning between cytoplasmic and ER chaperone-analogs are common, lead to the ER analogs as candidate-disaggregase machinery. Therefore, we hypothesised that the essential Hsp70-analogous ER chaperone BiP can be responsible for the organelle’s disaggregation activity. BiP’s candidacy for this role is further supported by its posttranslational/transcriptional response to ER stress, a condition in which we observe the disaggregation activity (Fig. 3). Namely, the UPR upscales BiP abundance and modulates its activity by amending the chaperone’s posttranslational modification and oligomerisation status23 prior to its upregulation and ER expansion. Specific elimination of this key endogenous molecular chaperone by treating cells with Subtilase cytotoxin (SubAB) considerably augmented the probe’s aggregated fraction (SubAB is a toxin from Shiga toxigenic strains of E. coli with a proteolytic A subunit that specifically targets BiP and B subunit responsible for internalisation and retrograde trafficking of the toxin to the ER24, Fig. 4a–c). Elimination of calreticulin, a central chaperone of the parallel BiP ER protein folding-assisting system, by KO25 did not affect the HT-aggrERaggregation load (Supplementary Fig. 10), arguing against the possibility of a generic aggregation enhancement of compromised protein folding. The aggregation-enhancing effect of BiP neutralisation with SubAB was exacerbated by stressing the ER with tunicamycin (Fig. 4a–c).

HT-aggr disaggregation by BiP in cells.

a FLIM images of live CHO-K1 cells stably expressing HT-aggrER (K73T), untreated, treated with subtilase cytotoxin AB (SubAB at 0.4 μg/mL) or with SubAB plus tunicamycin (Tm at 0.5 µg/mL) for 24 h, representative images from three independent experiments. b Quantification of the relative number of cells with FLIM-detected aggregates in images as in (a). c Quantification of the fraction of the cell area occupied by aggregates in images as in (a). d FLIM images as in (a) for cells transfected with CRISPRa vectors with specific gRNA targeting BiP promotor or with unspecific sequence (mock), representative images from two independent experiments, see Supplementary Fig. 11 for CRISPRa validation. e quantitation of aggregates as in (b). Mean ± SEM, n = 6, 6, 4 independent fields of view as in Fig. 3 for (b, c, e), respectively. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, unpaired T test (two-tailed).

To test whether elevation of BiP expression would reduce the aggregation load, we enhanced transcription from its genomic locus using CRISPR/Cas9 activation (CRISPRa). This approach allows added expression enhancement of targets with high endogenous expression levels, such as BiP (unlike ectopic, exogenous c-DNA in-plasmid delivery), and achieved approximately a three-fold increase in BiP expression at the RNA level (Supplementary Fig. 11a–c). The CRISPRa upregulation led to a significant decrease in the probe’s aggregation load (Fig. 4d, e). These observations support the BiP’s role in disaggregation. Further, they point to the significance of a balance in BiP quantity for native protein folding avoiding aggregation—through the increase in the levels of unfolded proteins (e.g. as a result of HT-aggrER overexpression) is successfully offset by an increase in BiP, restoring/preserving homoeostasis, its elimination cannot be thus be offset.

In vitro reconstruction of BiP-mediated disaggregation reaction

To further ascertain BiP’s capacity to facilitate disaggregation, we sought to reconstruct this reaction in vitro. Since J-Domain proteins (DnaJs/ERdjs) modulate HSP70/BiP activity and are crucial for recruiting the chaperone to its substrates, we fused the HT-aggr probe to a minimal generic J-Domain26 (HT-aggr-JD), a solution to enhance BiP ATP hydrolysis mimicking natural BiP/co-chaperone/substrate dynamics overriding the uncertainties associated with substrate specificities of the diverse J-proteins. The JD fused to HT-aggr appeared functional as it recruited BiP and interfered with BiP’s ATP-induced oligomerisation27, unlike HT-aggr without JD (Fig. 5a). Critically, the tendency to form aggregates upon mild heating was preserved in the HT-aggr-JD fusion (Fig. 5b). A heat ramp traced by static light scattering showed that incubation at 53 °C suffices to drive aggregation of HT-aggr-JD to completion (Supplementary Fig. 12a, Fig. 5b magenta trace). Based on these, we presumed that aggregated HT-aggr-JD, with its J-domain in cis, can allow observing the chaperone’s capacity, if it exists, as a disaggregase core. Indeed, the aggregated fraction of the probe attracted BiP WT but not its substrate-binding deficient mutant (BiP V461F, Fig. 5c, reflected in a higher absorbance peak of the aggregated fraction in the presence of BiP WT). Conspicuously, the aggregation fraction of the mixture diminished over time in favour of low molecular weight species (Fig. 5d). To unmix HT-aggr-JD aggregation status in the BiP/substrate mixture, we monitored the probe through its ligand’s fluorescence. Consistently with the UV-absorbance readings, this showed a BiP/ATP and time-dependent shift from aggregates towards smaller species (Fig. 5e). In the absence of BiP, or if the chaperone’s ATP-fuelling is not provided, the aggregates not only remain stable but continue growing to a point where they are too large to pass the chromatography filter (Fig. 5f, Supplementary Fig. 12b) but readily detectable by dynamic light scattering analysis (Fig. 5f, inset). The same behaviour was observed when the aggregated probe lacking J-Domain was provided as a substrate (Supplementary Fig. 12c). These results indicate that ATP-fuelled BiP can unravel pre-formed protein aggregates. It is worth noting that the in vitro measurements do not recapitulate the kinetics of this process accurately as BiP-assisting machinery is challenging to represent in all its complexity.

ATP-driven HT-aggr disaggregation by BiP in vitro.

a Protein absorbance traces (280 nm) of BiP WT (50 µM) alone (grey), with native HT-aggr (dark blue) or native HT-aggr, fused to J-domain (HT-aggr-JD, 10 µM) (light blue), resolved by gel filtration chromatography (10–600 kDa fractionation range). b Traces as in (a) of native HT-aggr (green), native HT-aggr-JD (light blue) and heat-aggregated HT-aggr-JD (53 °C, 20 min, 10 µM) (magenta). c, Traces as in (a, b) of aggregated as in (b) HT-aggr-JD, incubated with BiP WT/ATP (magenta) or BiP V461F/ATP (orange), a substrate-binding deficient BiP mutant. Note the increase in the main peak of the aggregated HT-aggr-JD (pale red) upon the addition of BiP WT/ATP only, indicative of its recruitment to the aggregates. d Traces as in (a, b) of aggregated as in (b) HT-aggr-JD, incubated with BiP WT/ATP for the indicated periods (4 h, magenta; 24 h, orange; 48 h, light blue). e Fluorescence traces of chromatograms as in (d) this time exclusively detecting HT-aggr-JD (pre-aggregated) through the fluorescence of its P2-halo ligand label (HT-aggr-JD, pale red; 4 h, magenta; 24 h, orange; 48 h, light blue). f Fluorescence traces of chromatograms for the P2-labelled HT-aggr-JD (pre-aggregated) in the absence of BiP for the same time course and trace’s colours as in (e). Fluorescence was measured for discrete data points, 0.3 mL each. Dynamic light scattering measurements showing the hydrodynamic diameter (Dh) of P2-labelled HT-aggr-JD (pre-aggregated) for the same time course were plotted in the inset to unveil the growth of the aggregates in the absence of BiP and explain why aggregates are retained in the pre-filter of the column leading to a decreased amount eluted over time. The measurements in (a–f) were performed in the presence of ATP (3–9 mM), which elutes at 20.2 mL, fractions omitted from the chromatogram.

Collectively, the findings of the current study reveal that the ER stress response programme contains the arm of inducible disaggregation. This complements its ability to preserve proteostasis by enhancing folding and reducing the load of client proteins (by chaperone expansion and attenuated protein synthesis/increased degradation, respectively). The three-layered PN response explains the organelle’s ability to maintain high fidelity protein manufacturing inducing disaggregation in a space crowded with nascent/folding species.

Though one cannot exclude a possibility of additional disaggregases’ involvement, the BiP system appears the only ER-resident molecular machine with such a potential. Mechanisms of BiP repurposing from a holdase/foldase-like chaperone to a disaggrease may hold clues to identifying strategies for antagonising toxic aggregates/seeds that evade the unstressed system (e.g. A-beta oligomers28).